Why Either/Or Thinking is Dangerous

Here’s a quick quiz – see how you do:

- Do people love change or hate change?

- Are big companies more innovative or are small ones?

- Is innovation good or bad?

- Is growth good or bad?

- Is Google making is stupid or smart?

All five questions have the same answer: both.

How did you do?

I was struck by the response to my post Actually, People Love Change. I had a surprisingly large number of people say “No they don’t!” That kind of missed the point of the post.

The point that I was trying to make is this: there are some changes that people actively seek out. They view these changes as good. Yet we know that in many cases, people strongly resist change. They view these changes as bad.

So you can’t categorically say that change is good, or that change is bad – it’s both. The challenge is that you have to figure out type of change you’re dealing with in each particular case. You have to categorize the change.

Classification is an incredibly important tool when you’re dealing with complexity.

It’s complexity that led Theodore Sturgeon to develop Sturgeon’s Law:

Here is how Sturgeon phrased it:

I repeat Sturgeon’s Revelation, which was wrung out of me after twenty years of wearying defense of science fiction against attacks of people who used the worst examples of the field for ammunition, and whose conclusion was that ninety percent of SF is crud.

Using the same standards that categorize 90% of science fiction as trash, crud, or crap, it can be argued that 90% of film, literature, consumer goods, etc. are crap. In other words, the claim (or fact) that 90% of science fiction is crap is ultimately uninformative, because science fiction conforms to the same trends of quality as all other artforms.

His short form of this reflects the thinking behind the Tao as well:

Nothing is always absolutely so.

Everything that’s black contains some white. Everything that’s good contains some bad. Change can be mostly bad, but sometimes good. Or vice versa.

Either/Or thinking is very dangerous in a complex system – precisely because nothing is always absolutely so. And, for better or worse, we live in a whole set of complex systems. We have to figure out how to move beyond Either/Or thinking.

So how should we respond to this?

Here are some ideas that can help:

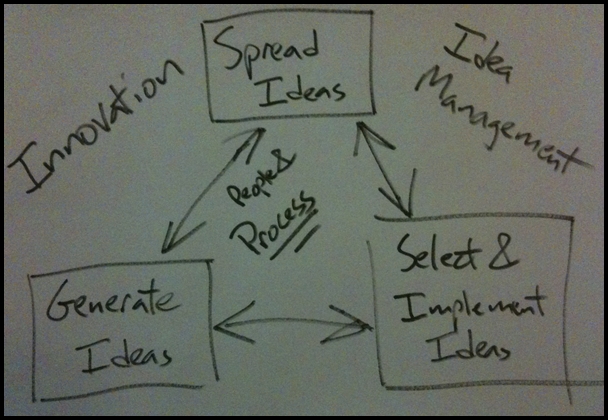

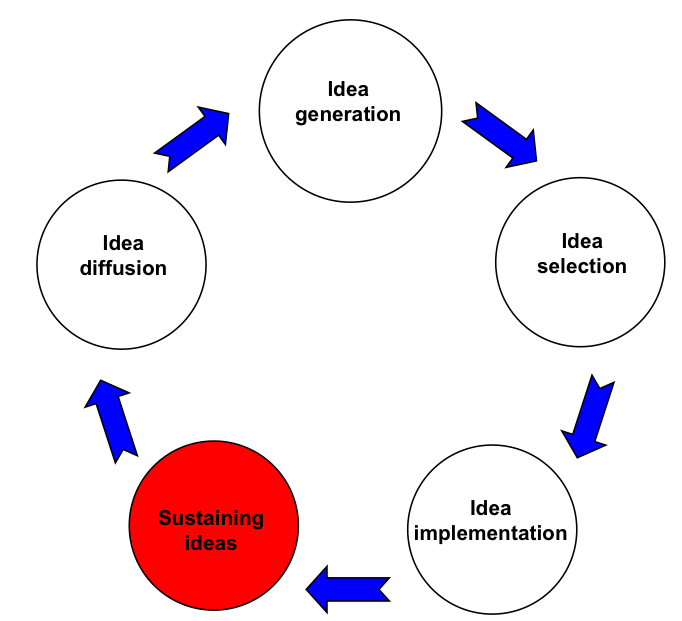

- Classification: how do biologists learn about how the world works? The first step is always classification. They can’t say anything if they can’t accurately tell what type of things are interacting with each other. That’s what The Innovation Matrix is – a classification tool.

- Study the part with the outcomes you want: we know that most large firms struggle with innovation, while some have become very good at it. What makes them different? Figuring that out is a classification challenge. One way to attack this is with The Positive Deviance approach:

Positive Deviance is based on the observation that in every community there are certain individuals or groups whose uncommon behaviors and strategies enable them to find better solutions to problems than their peers, while having access to the same resources and facing similar or worse challenges.

The Positive Deviance approach is an asset-based, problem-solving, and community-driven approach that enables the community to discover these successful behaviors and strategies and develop a plan of action to promote their adoption by all concerned.

Or, alternately: - Pay attention to outliers: In complex systems, outliers matter – a lot. That’s why thinking about averages is so dangerous. If we take Sturgeon’s Law seriously, the average science fiction is bad. But as he says, that’s uninformative. The critical question is “how good is the best Sci-Fi?” It turns out that the best is pretty good – the outliers a lot more important than the average.

Absolute statements get more attention. That’s why I named that post “Actually, People Love Change” instead of “Sometimes Change isn’t so Bad” or something equally wishy-washy. But the truth of the matter is that reality isn’t absolute. Neither black nor white. Neither either nor or.

It’s “both.”

Developing some skills to deal with “both” is pretty essential these days.

Read more from Tim here.

Tags: Change, Innovation, Tim Kastelle